Making commitments & the Principle of no surprise

Making everyone happy as a Product Manager is impossible. In any company, small or large, resources are too scarce for each request to be fulfilled. Product-lead companies solve that constraint by making product managers responsible for setting expectations and making promises. Unfortunately, product managers too often fail under pressure and give faulty commitments. That has dire consequences, resulting in a breakdown of trust between individuals and teams. Whoever has worked in a low-trust environment knows the impossibility of building a long-term strategy. To avoid this outcome, I advise product managers to use the principle of no surprise when interacting with others.

Product-lead companies put product management at the intersection of competing interests. Marketing, Sales, Engineering, Design teams compete for finite resources. Worse, in highly changing environments like in a startup, it’s expected for teams and individuals to fail on commitments made. In this setting, product managers’ commitments are the organization’s binding agent. Planning and strategy for teams can only revolve around these commitments.

Unfortunately, the practice of making effective commitments is either unknown or ignored.

Making commitments

Unclear requests lead to unmet expectations. One party will feel that they completed a task, and the other will believe they failed. Clarifying the request before committing to anything is imperative. At a minimum, the request should include an unambiguous objective/task and an element of time when the job is expected to be completed.

As a counter-example, take the request “Do you agree to help the Marketing team with user growth?”. Committing to this request would be a mistake. The timeframe is unclear; is it helping for a week or three months? The objective is undefined; do they need help to change a button or rebuild the entire website?

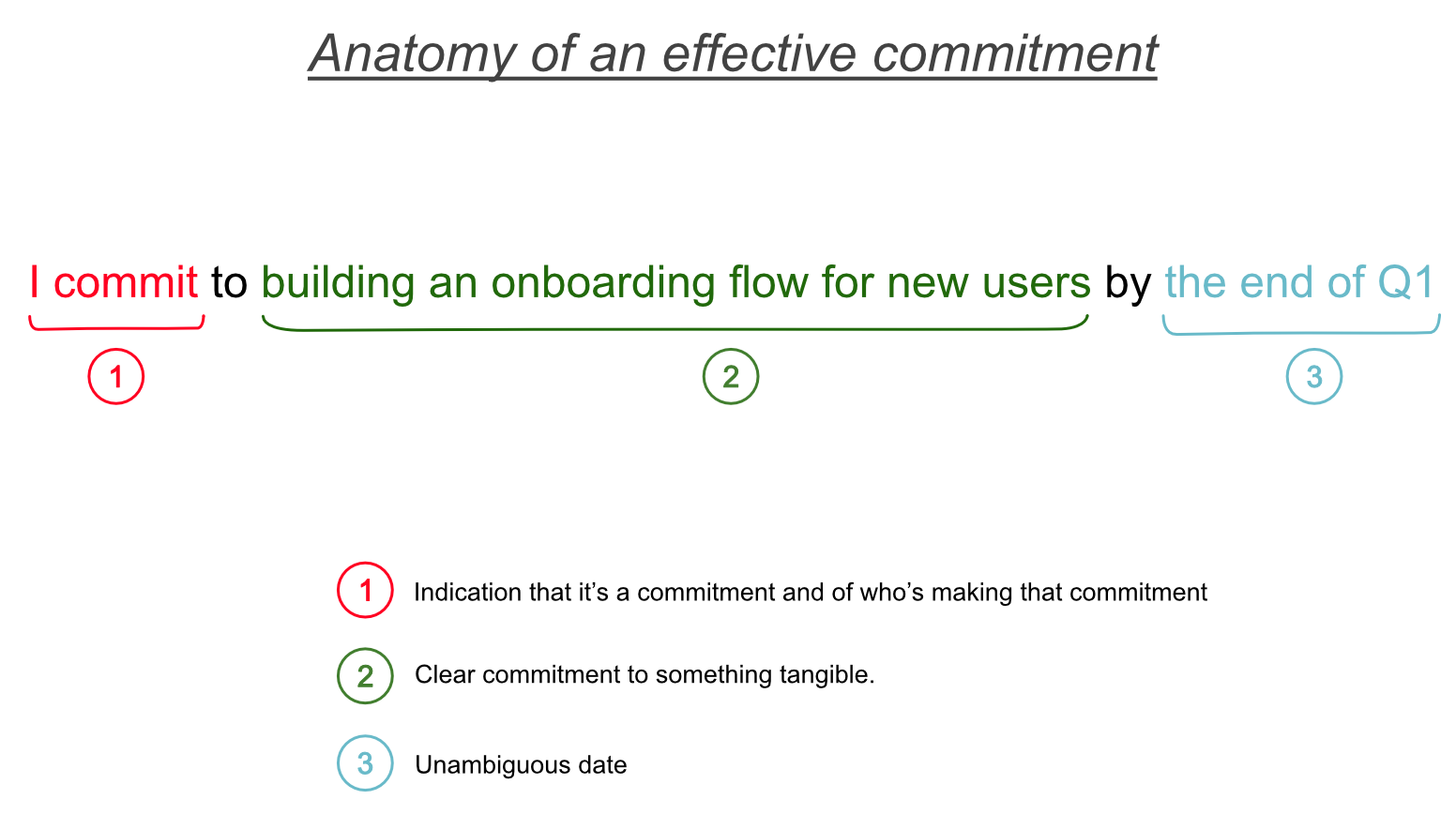

The second rule is to voice (or write out and share) an explicit commitment. If you’re not used to the practice, it will feel awkward at first. It’s straightforward. After clarifying the request, repeat back the commitment to the person. The goal is to indicate you’re making a commitment and what that commitment entails.

I like to use the sentence “I commit to doing X by Z.” X is the object of the commitment, and Z is a date.

For example, an explicit commitment will look something like this.

“I commit to building an onboarding flow for new users by the end of Q1.”

Failing on your commitments

It’s natural to fail on some commitments. Failing on commitments is not indicative of your shortcomings as an individual. Commitments are not suicide pacts; they’re the scaffolding to build yourself as a dependable, high-integrity individual.

How to handle failing on a commitment? First, communicate when you’re about to fail a commitment. Ideally, failure to commit is shared early enough that it comes as a warning, giving time for people to prepare and plan around it. Weekly or monthly meetings are great to update on the status of commitments, especially failures.

Once it’s clear that you’ve broken a commitment, make an effective apology. Effective apologies are potent tools to rebuild trust and its elements are straightforward.

- The apology must be sincere and personal. Acknowledge that you made a commitment and failed, and be the one reaching out directly.

- An effective apology provides context without sounding defensive or that you’re pushing the responsibility on someone else; remember, you’re the one that’s committed; it’s not your team.

- Lastly, it’s essential to inquire about the consequences of the broken commitment and work on potential remediation with the other person when possible.

Unambiguous commitments and healthy failure modes constitute the principle of no surprise, and a foundation for being perceived as a dependable individual. Product managers perceived as highly dependable have a powerful influence over other team members. They are trusted and powerful agents of change in any organization.

While the principles above appear stiff and awkward at first, they become second nature through continuous practice. Better yet, applied to your personal life, they are a foundation for healthy professional and personal relationships.

0 Comment